I first started reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved on Buffalo, New York’s one-street subway. Given our most recent battle of the books, maybe it’s fitting that I carried the book underground in order to read. It was 1995, my heart shattered to pieces once again by lost love, and I had a seven-month buffer until heading off to my begin by PhD program.

I found Morrison’s novel incredibly difficult because of how different it was (“novel” does mean “new” after all!), and I would ride the subway downtown, bewildered but enthralled, to my job at HSBC where I spent the day tracking down bad Canadian checks. I worked in Buffalo’s tallest building. You could see Niagara Falls’ mist from the upper-floor windows. I worked on a massive floor where all of my fellow employees (about 60 or 70) were African-American women (we talked openly about race with each other, and their preferred term was “black”).

The job itself was okay, but my co-workers made the time worth every minute, and we passed the hours talking about music (Biggie, Tupac, or Tribe?), gossiping about work romances, and then finally a woman named Jamille asked me what I was reading (they knew I was heading off to grad school). I answered “Beloved,” and she and others responded, “What’s that, a romance? What’s it about?” I tried to explain Beloved (ironically, the city I would be moving to was Cincinnati). I said, “Well, I’m not really sure.” This caused great confusion, as how could I not know what the heck I was reading, especially when I claimed to be studying this stuff called literature. The floor was divided into quarters, so a good 15 to 20 people were listening to me poorly try to explain the magic of this intricate novel. I imagine I sounded something like, There’s this woman who used to be a slave. She has children, but I am having a hard time telling if they are real. The woman, Sethe (which I pronounced “Seth”), and her friend Paul seem to like a place called Sweet Home, but they also ran away from there because it’s in Kentucky. There’s also a person named Beloved who just appears and people seem just fine with that. She also talks in ways I’ve not heard anyone talk. The room was quiet, until Jamille said, “What? That makes no sense. I am going to get this book and let you know.”

The days were still shorter that time of year, and at 5:00 I would walk into the wind-blown dark and travel back underground with Morrison’s novel. I finished Beloved and didn’t understand what happened but knew the ending had turned dark. I read the book again. Then another time after that. Years and years, a PhD and job offers later, I was teaching Morrison’s novel in literature classes (African-American literature was one of my exam areas, largely because of that journey which began on the subway).

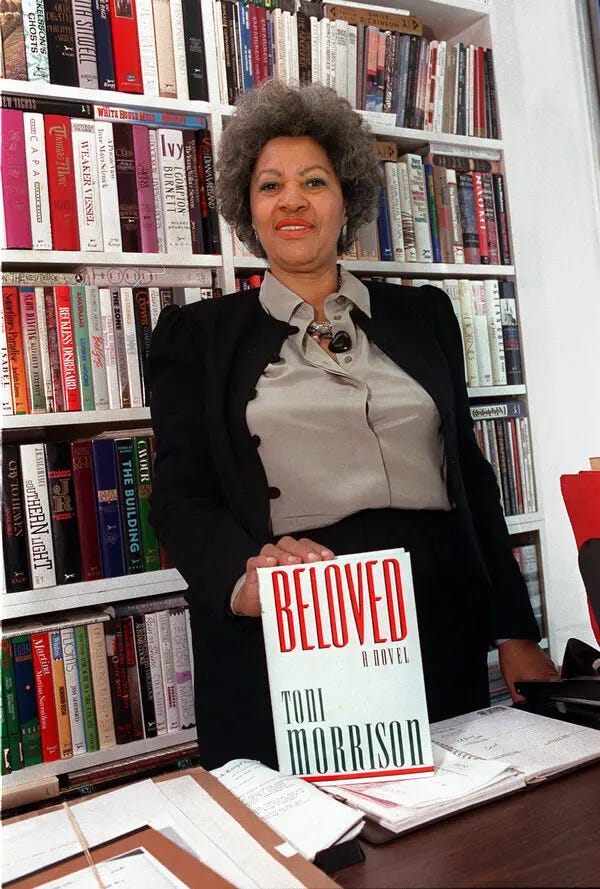

Yes, I teach books by Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Octavia Butler, Jean Toomer, W.E.B Du Bois, Etheridge Knight, Nella Larsen, Charles Chesnutt, and on and on. I teach these books because I teach, among other things, American literature. What I have listed above is American literature; the people and work inseparable from a rightful claim to a piece of that identity. Toni Morrison is the last American novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (Bob Dylan won in 2016). My prized possession is a book signed by James Baldwin, who passed the year I graduated from high school.

You know where I’m going. I do not have a credential in critical race theory. I do not hold an official position where I am “in charge of” diversity, inclusion, and/or equity. But I am a professor (my literal title), and again, I teach Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, and for that matter, William Faulkner. How could anyone possibly teach Beloved, The Fire Next Time, or Absalom, Absalom! and not talk about race, slavery, structural inequity, or what is simply our history? William Faulkner, a white man, and arguably one of the world’s greatest novelists, wrote a novel whose climax rests upon a single choice (spoiler free, promise): “if you choose taboo #1, I can live with that; if you choose taboo #2 (which involves race), I cannot and will act accordingly.” In other words, race is literally the raison d'être of one of America’s greatest novels.

We could go on. How does a history professor teach the second half of their survey course and skip over the American Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in America History and fought explicitly over the issue of slavery? In the most naive fashion possible, if someone asked me if I “taught CRT” I would say, “no, I teach literature and writing.” I imagine a historian could offer the same: “I’m not sure what you mean. I teach history.”

In the news last week was Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me being removed or “paused” from a school’s AP class. Now, I could certainly go down the claws out, argumentative path here—others already have that covered. I want to ask something a bit different: in my view, James Baldwin is hands down one of the best writers America has ever produced, even judging by his nonfiction alone. The style, the absolutely beautiful prose, the surgical argumentation, the wit, and the passion for both historical knowledge and change. How could I possibly teach any of this work and not talk about race? (And why would I want to?) What am I supposed to say? Yes, let’s read something equally beautiful but less controversial…like Giovanni’s Room. It is a disservice for anyone who wants to understand our country’s literature to not read multiple Baldwin texts. The examples are endless. If someone had stepped in and denied me the opportunity to read Octavia Butler’s Kindred, I’d simply be a lesser person. Kindred doesn’t make me ashamed of who I am; it doesn’t make me hate myself or cripple me with guilt—it brings me joy and wonder and, above all, perspective as a clear doorway to knowledge. I marvel at Octavia Butler, who could sit down and produce such a miracle, or beloved, of a book. (My goodness, I wish I was that smart! What a book!)

But I find myself despairing a bit these days. I fear needing to go back underground to experience challenging art. Back to the isolation of difficulty and incomprehension, where Beloved speaks and we do not understand or recognize the voice.

I need to find my way back to Faulkner.