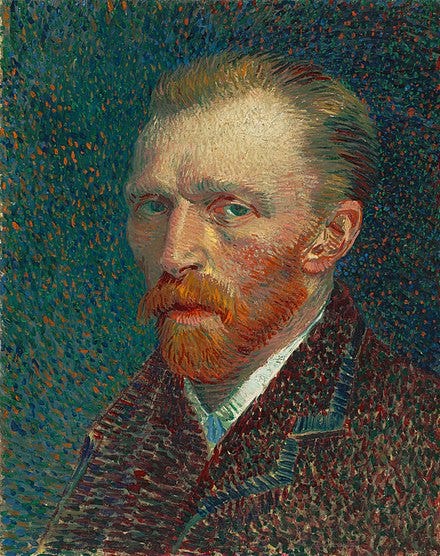

Tomorrow, July 27th, marks the anniversary of the day Vincent Van Gogh supposedly shot himself in the chest, walked home, and then lay in bed until dying in the early hours of July 29th. If you know about Van Gogh, shooting himself and then walking home in order to be utterly miserable would have been a very Van Gogh thing to do, or as folks say today, “on brand.”

I recently devoured Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s biography of Vincent Van Gogh, a simultaneously insightful, painful, and mesmerizing read. For a quick brushstroke, I’ll say this: never have I read about a more miserable, unhappy person, and never have I read about someone who produced so much beauty in such a short amount of time. The output is breathtaking. Wrap your head around this: nearly all the well-known paintings that comprise who we call “Vincent Van Gogh” were likely completed in a 5-year period. The man painted for literally less than a decade of his life yet produced nearly a thousand paintings (and I’m not even talking about the drawings and sketches, of which THERE ARE EVEN MORE); it was not uncommon for Van Gogh to complete more than one painting in a day—he was the artistic opposite of Leonardo da Vinci, who carried specific paintings around for years, maybe for a decade or more, adding tiny touch-ups along the way. The closest meteoric comparison I can conjure is Malcom X, who lived a mere 12-and-a-half years after his release from prison—Malcolm X’s entire public legacy was built in that short period of time.

The Van Gogh biography approaches 900 pages, and nowhere along the way, anywhere, is there a mention of guns until Van Gogh’s death. The effect is dizzying: you’re reading about and vicariously living in the world of the Netherlands, rural landscapes, urban and suburban Paris, Van Gogh’s contemporaries, the art of the times, and then, at book’s end the text’s first firearm emerges and one of the world’s greatest painters is dead at age 38 by gun violence. Gun violence! In Auvers-sur-Oise, which was a quiet Paris suburb! I’m willing to venture Van Gogh was the only death by gun violence in Auvers-sur-Oise that year, as well as for many of the years preceding and following. It’s crazy. Yes, guns existed. Wars had been fought. Samuel Colt’s revolver was patented in 1836. But Vincent Van Gogh, on the receiving end of gun violence while stumbling around the countryside with his arms full of canvasses and paint? This is an ontological shift.

Here’s where things turn interesting. I recently went to Chicago and was able to visit the exhibit Van Gogh and the Avant Garde: The Modern Landscape, which also included work by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Emile Bernard, and Charles Angrand. The exhibit, gorgeous and thorough, made me weepy because I’m like that. On the walls was a timeline to guide you through the exhibit, with the inevitable conclusion being Van Gogh’s death, which the Art Institute of Chicago described as death by suicide.

However, Naifeh and Smith’s biography posits a different theory of Van Gogh’s death—that he was shot by a 16-year-old boy named René Secrétan. There were no witnesses, recovered gun (that is, until 1965), or real investigation, so the official line is still death by suicide. (Note: if Van Gogh did shoot himself, I still consider this gun violence, as do many others who do statisical work on gun deaths.)

What intrigues me about the René Secrétan theory is not whether it’s true, but the American-ness of the theory, which is what makes it so plausible to the imagination. As it happens, Van Gogh’s death coincided with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which toured Europe four times between 1887 and 1892, which spread a wild west and “Cowboy and Indian” mania among many Europeans, especially children—Secrétan himself attended one of the shows in Paris. Put another way, kids wanted to play with guns. And guess what: René Secrétan had access to a gun. While vacationing in Auvers-sur-Oise, Secrétan and his friends are described by Naifeh and Smith as being caught up in the wild-west mystique, even dressing the part with a cowboy hat and chaps, as well as a small gun with which they would occasionaly hunt squirrels.

The biographers’ scenario is that Van Gogh possibly stumbled upon Secrétan and his friends, which led to some taunting and an argument. (Throughout Van Gogh’s adult life, he was picked on by children and adults, often referred to by people as “that painter” or the weird, loner guy who was always stumbling about and asking people to sit for a portrait.) The theory, as you might expect, is that this led to René Secrétan firing the gun and, upon realizing what had just happened, he and his friends ran away. The Secrétan family left town for home soon after, and that was that. Of course, based on what I read, Van Gogh is also the type of person who would say he shot himself even if he hadn’t (his mental state suffered severe fluctuation), and outside of his mental health struggles, he also seemed irascible enough to, for example, walk 100 miles, deliberately shoot himself in the kneecap, and then walk all the way home just to prove a point about dedication or some other virtue.

I do not know what happened, and there are other sleuths who have already swarmed all over a case that has proved inconclusive. But my imagination is firmly on board with the scenario the biographers provide. Why? Because of course a gun would appear on the scene under the influence of romanticized and violent Americana. Of course a wild west show would draw huge crowds while one of the world’s greatest painters was nearby, still largely unknown. Of course America and the idea of gunplay would appeal to the minds of the biographers, our obsession whooping and galloping its way through the world.

Even if he wasn’t murdered, Vincent Van Gogh died by gun violence. Even if that didn’t happen, the image of a French youth, dressed as an American cowboy, shooting an old man stumbling on his path toward yet another masterpiece, is a starry night of its own, illuminating a future with still so much painting to come before its completion.