Thank you to all subscribers! Please keep doing so, as I greatly appreciate it. You can subscribe here, and you can also share with others at the bottom of the post. Have a great day and don’t let the man get you down!

Just over a year ago, our family took our first real vacation as a family. No one else was coming with us. We weren’t visiting or meeting anyone. We were just going. Ourselves. And we decided to go big: we went to Maui, Hawaii.

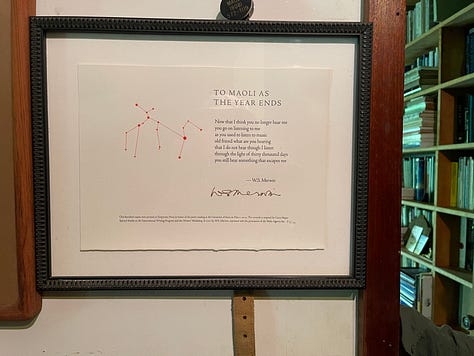

Yes, this was going to be an adventure, but semi-secretly, it doubled as a personal pilgrimage. The aptly named Haiku, Hawaii, since the 1970’s, had been the home of W.S. Merwin, a poet who means worlds to me. Merwin passed in March 2019, and his home and land, in order to preserve their integrity, were turned into a conservancy. Merwin died on the eve of the Coronavirus pandemic, so his home and land had, by the time of our trip, still remained largely untouched.

The site was still closed to visitors, but persistent emails professing love for Merwin resulted in us getting a private tour—the fact that the guide had a Wisconsin connection worked in our favor (cheese curds are a universal currency). Before getting to some photos, it’s important to understand some history and how it relates to the title of this piece: when Merwin bought the land it had been a pineapple plantation, stripped of all its trees. Think about that when you see the photos below. A particular sentence spoken by our guide has stuck with me: “99% of the vegetation you see in Hawaii is non-native to the islands.”

So, in addition to building a house (Merwin borrowed money for all of this; he was largely broke), he began to plant native palms and plants, one at a time, day by day, for what eventually amounted to over 40 years. It’s not quite right to say “one person” did this, as he married his wife Paula in 1983, thus doubling his workforce.

When arriving, we found ourselves standing in a rain forest. There were so many trees and plants that to call the place a “jungle” was appropriate. Our guide showed us a photo of the land, taken by Merwin, when it was first purchased. Nothing. Dirt. Empty. But over the course of their lives, the Merwins made a difference, and that was his stated goal—he wanted people to know that not only could one person have an impact, they could have a dramatic one. Behold.

Look at that. I do not have access to the “before” photo, but it was clear-cut land in order to support a pineapple plantation. Pineapple plantations look something like this…

And when Merwin bought his land, it was not being used anymore—so look at the above photo and subtract the pineapples, then compare to the gallery above.

Two people, day by day, planted a forest of native palms and plants where there was nothing. Botanists now come from around the world to study the native palms planted by the Merwins, as they no longer exist in many other places and they are rare evidence of indigenous life. (Merwin, unable to resist, did also plant mango trees, which are believed to have been brought from the Philippines in the 19th century.)

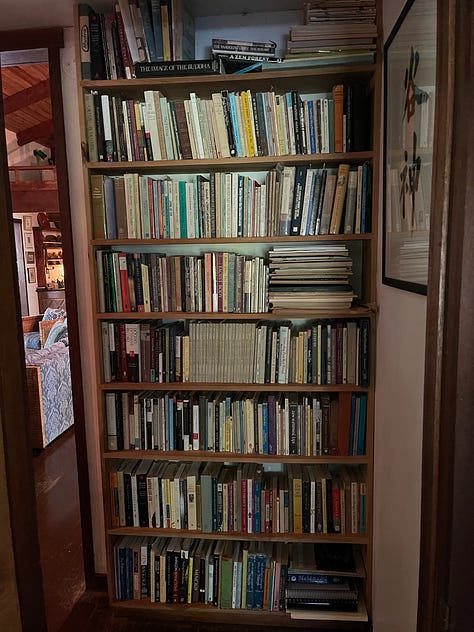

We were also blessed with a tour of Merwin’s home, which still felt lived in—dishes out, a glass still in the sink, letters and notes just sitting out for the reading. Our guide explained that no one, when Merwin was alive, was allowed in his study, but she would let us in as long as we agreed not to take pictures. It was a sanctuary, a temple, his bookshelves and references there for the viewing, a note to his dogs pinned on a corkboard, a letter from Robert Bly. Our guide mentioned off-handedly, “We are just now getting to work. I was flipping through one of his books and a letter from Sylvia Plath fell out. He loved to stuff letters into his books.” She showed us a photo of Merwin and Tracy K. Smith (then the U.S. Poet Laureate) sitting in his home and talking.

Merwin was said to wake before dawn each day and stroll to his meditation space (built a short walk away from the house; Merwin was a Buddhist and moved to Hawaii to study with a particular teacher) so he could listen to “the forest wake up.” Then he would write. Then he would plant whatever tree or plant that needed a home in the ground that day. Here are some photos of Merwin’s home (as agreed, none from his study).

Consider this Part I of a non-Merwin piece that I’ll post tomorrow. I write this because I feel that many people around me (and me included) are overwhelmed with bad news, feelings of hopelessness, saying to oneself, “What is it that I could possibly do that would matter?” Climate, daily gun violence, insurrection, the cognitive dissidence of the “supreme” court, gerrymandering, an open resurgence of white supremacy, online disinformation and hate—and the list only gets longer.

I left the Merwin residence with hope. And when taken metaphorically, the hope that any of us, individually or with others, plant a meaningful forest day by day that would grow into something wondrous. To paraphrase Rebecca Solnit, we must have hope in the dark. Not hope as a feeling, but as the tiny action of tiny hands, adding up, day by day.