My next free subscriber is number 100! So be the one and…

I believe many writers arrive at a point where they are confronted by what may or may not be a rule: Don’t write about your dreams. Don’t write about your characters’ dreams.

I definitely belong to the tribe that likes to break general rules, but I do find wisdom in this particular maxim. I guess I’d prefer to refine the “rule”: don’t write about dreams unless what you’re doing is superlative or at least fresh in some way. This is an Everest-high standard. That said, if Christopher Nolan had followed this rule he would not have written and filmed Inception, which would be a darn shame. Inception is superlative.

Everyone has weird dreams, me included. I once dreamt I was eating at a restaurant in the ocean. Checkered tablecloths were floating and bobbing on the water’s surface, and the diners were treading water while eating. I never wrote about it until the previous sentence.

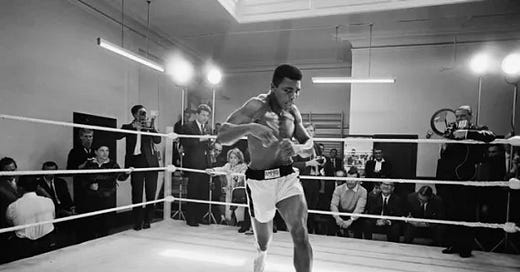

I did, however, once have a dream about Muhammad Ali, and I wrote a poem about it that was eventually published. The poem is below, and I will of course let you decide if I should have followed or ignored The Dream Rule.

But truly, the impetus for this post remains my question about the relationship between writers/writing and dreams. Are dreams off limits or fertile ground?

Dreaming Ali by Chuck Rybak It's not worth writing down dreams except for the one about Ali early 1970's Ali white shorts black trim Ali bouncing on his feet like a tapping man can tap bouncing on his feet like a hummingbird can hum sweating through in a one-bulb locker room where the man handlers have handled rubbed down a hard duo of dream-dancing legs rubbed down his brown, hope throwing arms taped each fist as tight and neat as a present that will tear open into everything you have ever wanted for yourself and he talks and chants and spits out prophecy in hot winds of cool call and response in hot winds that blow into the future of clash Ali talks the uncertain into certain Ali talks slaughter into triumph and you among the crew who massage and drum the limbs and the chest and the skin of Ali the crew who responds to his call in a muscular chorus of Uh huh, You, Indeed, It's true and Ali is talking, Ali is looking just beyond and what he says is hazy so fill it in because we've come this far Ali says, There is only this journey and this journey is now Uh huh Ali says, Who is the keeper of the eyes and the face You Ali says, Deliver these hands to the people who need hands Indeed Ali says, Even justice can disrobe and knock a man down It's true then you're waking up against your will mumbling mouthpiece waking up without Ali who should rumble pretty by your side forever and it's just you through the tunnel eyes opening to the taut air of expectation ready to fight for something in the spectacle and flashbulbs of our fearsome present

I loved your Ali poem!

I also think rules should be broken, but it would be fun to break rules if everyone broke them all the time!

My thoughts on dreams and writing are scattered.

For me dreams might be the starting point for something, but rarely make for a fully-formed story or poem. Of course, dreams can be brilliant sources of inspiration like Jung's Red Book. However, I do find it tiresome to hear most people's dreams. Maybe they just aren't good storytellers. I once wrote this about sharing dreams:

Why are you in Hell?

every morning I described

my dreams from last night

First, I agree with Mr. McBride: the Ali poem is a good one, suffering through other people's recounting of their dreams is tiresome, and the haiku is spot on. Oh, and yes, rule-breaking should be encouraged. But, second (and here I turn into the Quibbling Humanities-Fan), while I agree The Dream Rule deserves to be interrogated, I don't believe your Ali poem is the best test case, because it's identity as a dream poem seems, to me, to be pretty much . . . incidental. That is, if the reader hadn't been informed at the outset that what follows is a dream, would it still qualify? Would a reader be able to "figure that out?" Chop off the opening lines and what remains is a cool little scenario of Ali working out and talking in his signature way. But nothing happens that signals, "This is a dream" like, e.g., the surrealistic scene of floating tablecloths in your ocean-dining dream. Yes, your ending would have to be revised without the opening, but that would entail simply taking out more "telling" readers, yes, this was a dream. Notice how I slyly invoke another hoary rule that likely deserves interrogation: "Show don't tell," which does apply in this case: does the poem ever really "show" us its dream-iness? [Re: "Show don't tell": ironic, isn't it, that this is a rule that tells us not to tell.]

{Interestingly, the only time I've ever had to really deal with The Dream Rule involved the Duchamp story of mine that you remember. The original draft I submitted to the workshop had a long dream scene that Erin immediately told me to jettison because of The Dream Rule. I dutifully did so and the story did not suffer because of its absence. Several months ago, though, I happened to run across that draft and after reading the excised dream I thought, "Huh. That's not a bad piece of writing, and might have actually added some psychological depth to the whole proceedings." But will I ever reinsert it? Nah. The whole story was so thoroughly revised there's not really a place for it anymore. But the experience did make me question The Dream Rule. I think part of the appeal of the Rule is that it reinforces some Pursed-lipped Puritanical notion about the value of "hard work." Everything must be earned by dedicated, no-corner-cutting labor. When applied to writing, this means no dreams because since anything can happen in a dream, it gives a writer an easy way out of what otherwise might be a difficult writerly dilemma. Can't find the murderer? Well, just have a dream that provides the crucial clue. Can't figure out why a character acts the way they do? No problem, just dream the answer. Etc. And while my Calvinist upbringing makes me (unwillingly) susceptible to The Dream Rule injunction, I also resist the idea that dreams should be banned completely. My favorite part of the Harry Potter series happens in the final book. Harry has been zapped (again) by Voldemort and while he's unconscious he has a vision of talking with Dumbledore in an ethereal tube station.

“Tell me one last thing,” said Harry. “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?”

Dumbledore beamed at him, and his voice sounded loud and strong in Harry’s ears even though the bright mist was descending again, obscuring his figure.

“Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

So, yeah, dreams happen inside our heads, but that doesn't make them any less real, and shouldn't all real human experiences be available for writers to use?}