Is History a Palindrome?

I do have a smallish morning ritual. Yes, coffee is involved, toast of some kind, and then I read Heather Cox Richardson’s newsletter, Letters from an American. (Subscribe. Trust me; it’s worth it.)

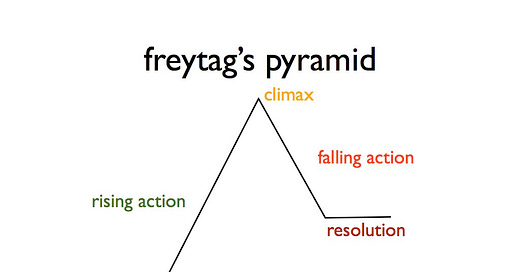

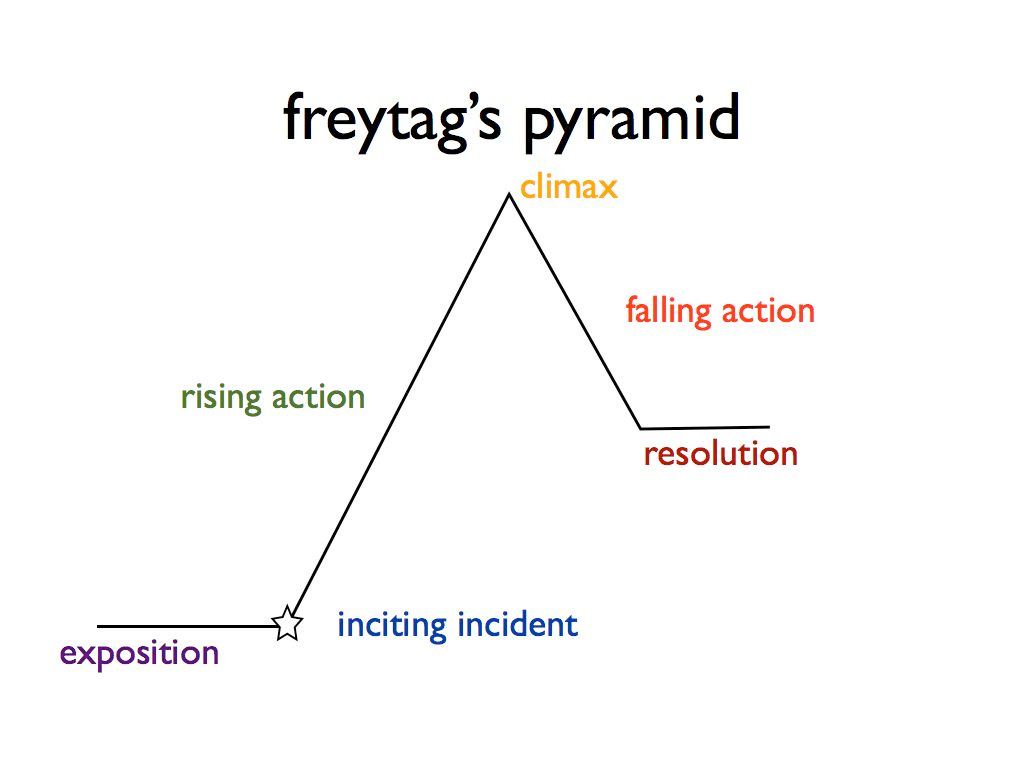

Many moons ago, I earned a double major as an undergraduate, with one of those degrees being History (the other, of course, English), and paired together they fed—and still feed—my interest in structures and my need to understand and diagram them (in graduate school this made be a poor postmodernist). You know, the plot arc and Freytag’s triangle (now upgraded to “pyramid”) and all that kind of stuff.

Heather Cox Richardson talks a lot about history’s structure in her newsletter—like what conditions might be required to clear the democratic stage for a would-be authoritarian—but she does it with language that’s more attuned to my interests: poetry. In fact, she writes, “Historians are fond of saying that the past doesn’t repeat itself; it rhymes.” I like the seeming simplicity of this complex comparison, especially when considering slant rhymes (often hard to hear) and identical rhymes (which is simple repetition).

As I’ve probably written before, when it comes to canonical American literature, I love William Faulkner. Faulkner himself was fascinated with history and his novels, especially their settings, often act as a staging of what he views as history and how it’s structured. The pinnacle for this is his novel Absalom, Absalom!, where the history of the Sutpen family plays out against the backdrop of what Faulkner views as the collapse of the American south, especially its mythos.

More importantly, there is a moment in the novel that is so weird, so incongruous, that I’ve come to read it as Faulkner’s theory of history’s shape: a palindrome. Faulkner is not known for brevity; he is known for density. Heck, one of the chapters in Absalom is a single, very long sentence. Yet, when we get the novel’s most crucial moment, the one we’ve all been waiting for—when the person of the present finally meets the person of the past, this is what we get:

And you are- ?

Henry Sutpen.

And you have been here – ? Four Years.

And you came home – ? To die. Yes.

To die-?

Yes. To die.

And you have been here – ? Four Years.

And you are – ?

Henry Sutpen.—Absalsom, Absalom!

That’s it. The full exchange and all its words nearly devoid of meaningful information. But the structure. A near-perfect palindrome. If you take the first and final two lines as a pair, the only difference lies with the phrase “And you came home— ?” Cut that phrase and you have a palindrome.

I may not know that much about anything, but I know me some William Faulkner. And what I see in this passage is a structural confirmation of Heather Cox Richardson’s saying that history rhymes—almost the same, but not exactly, a single consonant (or phrase) in some cases being the only difference.

Did January 6th feel like a Civil War of sorts? Did you know that, in 1939, over 20,000 Americans showed up for a pro-Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden? According to one article about that event:

The rally was sponsored by the German American Bund, an organization with headquarters in Manhattan and thousands of members across the United States. In the 1930s, the Bund was one of several organizations in the United States that were openly supportive of Adolf Hitler and the rise of fascism in Europe. They had parades, bookstores and summer camps for youth. Their vision for America was a cocktail of white supremacy, fascist ideology and American patriotism.

Check out the article’s photo and do your best to zoom in. There is a giant banner of George Washington and on either side of him there are banners bearing swastikas. Is this history or a Philip K. Dick novel? Why does the final sentence of the quote feel like a historical rhyme?

In the case of Absalom, Absalom! one palindrome of its history might look like this:

Have nothing

(Build) something

(Maintain) control over what’s been built

Zealously believe in the rightness of yourself and your actions

Make a critical mistake

Zealously believe in the rightness of yourself and your actions

(Lose) control over what’s been built

(Destroy) something

Have nothing

So, where are we now? I’ve spent the last few days reading about the damage enacted over time by the Supreme Court of John Roberts (maybe then we are at bullet-point six). Thus, I am trying to pinpoint our location in a palindrome whose material is too immense to understand (the exact position of Quentin Compson in Absalom, Absalom!)

Maybe that’s why I’ve been writing posts called “Can One Person Make a Difference?” Maybe that difference is breaking the palindrome and making it imperfect, a rhyme. Or maybe that person fits into the palindrome, and we have to keep waiting for the nobody to become somebody, by sheer force of will. The people who will do just enough to not be heroes.