As always, thank you to all subscribers old and new—this is a growing community and all are welome!

Yesterday, there was a piece in the New York Times called “Why Does God Keep Making Poets?” I could say a lot about the title, but I will leave that for another day.

For the piece, Tish Harrison Warden interviews Abram Van Engen, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, and their first order of business is what you’d expect—poetry being hard to understand and whether this closes the door on many new readers. Van Engen acknowledges that accessibility is a problem and that many potential readers feel that reading poetry requires some kind of special credential to unlock. He follows that admission by saying:

My own entrance into the world of poetry came about through a poem I did not understand, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” by Gerard Manley Hopkins. If you read that poem out loud, I think most people will think, “I don’t know what that means.” But also it’s apparent that it’s this beautiful music of words that he has put together.

I am here to provide a valuable service regarding Van Engen’s above claim: no. Completely wrong. The “beautiful music of words” is not readily apparent. If you start with this kind of magical thinking (say, as a teacher), that the mystical fumes of “beauty” will somehow rise and neutralize the value of comprehension, you will never get past square one. Ever. You will get a majority of people saying “I don’t get it” in reference to what is by far our most democratic art form.

So Let me tell you a story.

Initially, I went to college as an aerospace engineering major—my quick abandonment of this major saved countless lives and I am very proud of the public sacrifice I made in not working on anything that might fly.

As I made my way into English and writing classes, something that I loved but did not realize one could major in, I initially struggled, especially with comprehension. The British Lit survey was especially challenging in this way. I went to SUNY Buffalo for my undergraduate education—historically, a poetry mecca—so I was especially lucky to be in the same building with poets like Robert Creeley, Susan Howe, and Carl Dennis—Carl Dennis, who I worked with the most, eventually won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for Practical Gods in 2002.

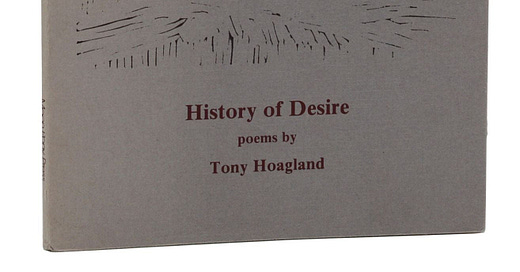

So I find myself in a poetry class with Professor Dennis, and there is a weird book on the syllabus—History of Desire by Tony Hoagland. It didn’t look like other books—it was a chapbook (I didn’t know what that meant), as his first full-length collection had not yet been published. All I knew is that Carl Dennis somehow knew Tony Hoagland and believed he had a future ahead of him; he was correct.

History of Desire pretty much blew the top of my head off. I probably read it a hundred times, eventually underlining every line in the book, plus marginalia! (I view my 19-year-old self with a mix of embarrassment and love when looking back at my notes.) Why did I respond this way? Why this profound impact? Easy. Tony Hoagland was the first living poet I had ever been assigned to read and I could understand his poems. So, as they say these days, “full stop.” Hoagland wrote about things I understood—love, passion, rock and roll, moving into a world where sex was real, jealousy, parents, and fragility. And even with all those ingredients, he was also funny! What more could I ask for? Finally, poetry inviting me in as a reader! The subject matter and accessibility made that happen, not the wafting upwards of beauty’s ethereal fumes (that would come later—Sylvia Plath, herself an accessible poet, really taught be about the beauty of rhythm and sound).

I cannot express enough how important it is to be invited into poetry as a genre. Accessibility was poetry’s extended hand, reaching out and connected to a living person who could cry and laugh and bleed, just like me. Have we learned nothing from slam poetry?

I followed the rest of Tony Hoagland’s career and was fortunate enough to briefly meet him at AWP (he had no interest in talking with me, as he had been joined by a friend at the table where he was supposed to be signing books). He signed my copy of Donkey Gospel, as well as the nugget of a chapbook called Talking to Stay Warm. I confess that with each book he published over the years I connected less and less, though there would always be at least one poem that brought me back, because I could say I was there at the beginning.

I was also incredibly sad when Hoagland passed away in 2018. I cried, remembering with gratitude the world to which his work had introduced me. The poet himself was vulnerable, funny, and often judgmental, and I understood all of it and the reasons why. I could engage without having my first intellectual step be, “Do I even understand this? Surely it must be…great?” Of course I moved on from there, into the world of deep image poets, Rimbaud’s Illuminations, the Romantics, Language Poets, Beat Poets, the deeply abstract and yes, even Gerard Manley Hopkins.

But if you want people to read more poetry, give them an invitation. It should be an invitation that, when pulled from an envelope and opened, is clear about when and where the party will be held.

The very first time we met, during an "orientation" class break, you recommended Tony Hoagland to me and I believe I almost immediately went forth to acquire a volume of his poems (or maybe you loaned me a copy?). I do know that I tried to write a review of "Donkey Gospel" for Rettberg's "Books-in-Chains" website (in which I declared Hoagland's first book, "Sweet Ruin" as "the best book of poems I'd read in 1995"). The review was a solipsistic mess, unfortunately, and Rettberg wisely decided not to use it. Prompted by your little memoir, I've been trying to identify my Hoagland, the poet and / or poem that "invited" me to the world of poetry, and, embarrassingly enough, I'm failing. Or rather, some of the candidates I've considered would be too embarrassing for me to claim as being the source of my current involvement with poetry, either too awful for me to admit having been influenced by, or too lofty to be believable as an inaugural touchstone. I will ponder this matter further.

After writing several hundred words purportedly revealing my "invitation in," I casually ran my hand across my trackpad and the whole page disappeared, apparently to some irretrievable zone. I'm too old and too disgusted to rebuild that exotic edifice. So, here's the short version: 3 possible candidates, or rather, 3 likely entry points, each entry taking one further into the mansion. 1) Richard Brautigan's poems, haiku-adjacent epigrams drowning in hippie sauce, often clever, frequently delightful; 2) <and believe me, I admit this only because I can hardly believe it myself> Rod McKuen's "Listen to the Warm"--Rod's syrupy, sentimental, nearly-epic sequence of poems celebrating his cat "Sloopy" was simultaneously astounding ("You can write poems like this? About this?") and the most ridiculous piece of dreck imaginable ("You can write poems like this? Are you kidding?"). Both Brautigan and McKuen wrote poems that declared: "See, poetry isn't that hard. If I can do it, why not you? It's a cinch! You know, just break up sentences into lines, here and there: voila! a poem!" --- and my resistance to those notions that poems were just tight little, cute little word trinkets, simple to write, simple to understand, led to ---- 3) T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land." No joke. That's really the poem that clinched the deal for me, and I've been obsessed with that poem ever since. I could write more about all three of these poets and their poems, and how and why they're important to me, but time is short and I don't want to be . . . that guy . . . the one who doesn't know when to give it a rest, already.