I’ve been thinking a lot about institutions and how, no matter the people that inhabit their structure, their language and actions will eventually be dictated by the institution (say, higher education or contemporary politics). Put another way, good and moral people will do and say unkind things in the name of institutions, often framed as “tough choices” and the numerous other phrases synonymous with such behavior. I am trying to untangle whether this is good or bad, or requires case-by-case analysis, but the key word is “untangle,” as this is a piece that’s really about thread.

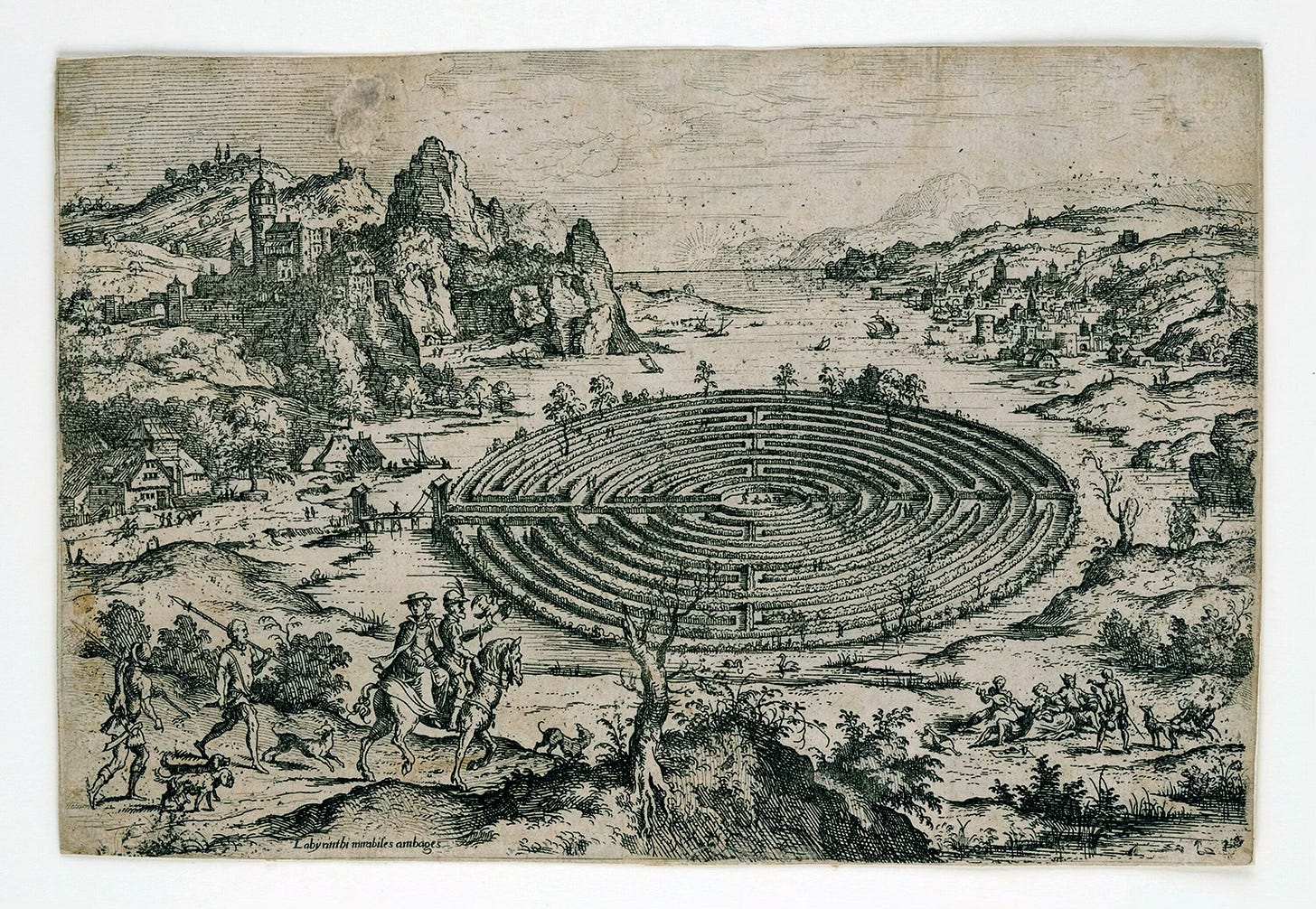

When I think of institutions, especially those with long histories, I think of Daedalus’s labyrinth and the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, which I’ve already spoiled by saying it’s really a narrative thread about a piece of thread. What do I mean?

Here’s a quick summary of Theseus and the Minotaur…

Minos, the King of Crete, demanded that Athens, every nine years, deliver seven young men and seven young women to Crete as a sacrifice (there’s more backstory as to why), with the Athenians ritually sent into the labyrinth to be devoured by the Minotaur. Theseus, an Athenian youth, essentially “volunteered as tribute” (think Katniss Everdeen) to prove his worth to his father, King Aegeas, and journeyed to Crete as one of the seven males. In Crete, Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, falls in love with Theseus and conspires to help him to escape the labyrinth—she does this by giving Theseus a ball of thread, which he unwinds during his progress into the maze’s interior, so he can eventually find his way out.

Here’s the myth’s under-examined thread: the labyrinth, an institution, is the story’s true antagonist. Ariadne does not help Theseus defeat the Minotaur. The reality is that even if Theseus is victorious, he will still die in the labyrinth (the institution) because he will never find his way out; this is true even if Theseus had gone in to pick blueberries. Theseus indeed finds his way out by way of Ariadne’s thread, but then a curious thing happens: he believes thread is conceptually no longer relevant. He leaves Ariadne, who he promised to take with him, behind and sails home. Now, Theseus was supposed to signal a successful journey by sailing to port in Athens flying his white sails. Instead, Theseus somehow forgets this thread, leaves his black sails in place, and thus his father, King Aegeus, believes his son is dead and commits suicide by throwing himself into the sea, which is then renamed… The Aegean Sea.

What are the sails made of? Thread.

Theseus believed the labyrinth—or institution—was self-contained and didn’t extend into his exterior life and home. He believed that Ariadne’s thread was the only thread required to reach safety, but the thread proved to be longer and incorporate more pieces than imagined; the result is tragedy. Theseus never truly escapes the Labyrinth because once he has entered its walls, they, as an institution, stay with him beyond his physical departure and become part of his life, mind, and thinking. By only following the (narrative) thread out of the labyrinth and not following its length—in the form of the sails—all the way back to Athens, his actions/lack of action, no matter how good a person Theseus might be, results in harm to others, in this case his family and the institution that is the governmental structure of Athens.

Is this not the case with many of our institutions? That once you enter their structure you can never quite escape their presence, much like Theseus hasn’t quite left the labyrinth behind? What you think might be a small victory—a gaining of praise or respect—proves ephemeral, maybe even fictitious, though the structure, language, and demands of the institution itself are not ephemeral, remain with you, and become part of you. To enter the labyrinth is to, paradoxically, always be inside its walls, even after exiting.

How do we know this?

Have you ever lay in bed at night, brain racing about some conflict, issue, or argument related to, say, your workplace? Was your heart racing? Were you up until 2:00 or 3:00? Have you ever invented or anticipated the institutional arguments you might have, and ruminated on those imagined conflicts in the dark? Have you ever carried your bad mood—those black sails— from the institutional labyrinth back into your home? We’re all a bit of the Minotaur, suffering defeat inside the actual walls. We’re all a bit of Ariadne, left behind by an idealism we thought we could preserve. We’re all a bit of Theseus, unknowingly bearing the labyrinth’s institutional message into the spaces we enter after leaving the walls behind. And we all miss the most important thing of all—the thread is this story’s purpose. This story is, too often, our story.

What’s the remedy? Remember the thread and that you are still following its trail. Remember to switch the threads from black to white. Only then can you truly find your way home. You have to remember the thread by always keeping it front of mind, and you do this by remembering an essential quality of institutions—they can never love you back. They’re not supposed to. Their purpose is to exist and be durable well beyond whatever individuals may inhabit their structure. This durability can be beautiful, and it can also be terrifying.

Knowing where the threads are and never letting go of them are the best chance you have for a continual return to goodness and integrity. After all, the threads were given to Theseus by other people and were meant to lead him back to them.

Put another way, trust people who knit. They’re on to something.

I love this ingenious and relevant reading of Theseus and Ariadne's story. I love Mary Oliver's treatment of the story in "The Return" (https://thesewaneereview.com/articles/the-return) *except* that her beautiful poem does not do justice to Ariadne. I appreciate that you keep the story going to Theseus' abominable choice to ditch her.

Interesting essay. Enjoyed it thank you!